[This is the text of my keynote on 31 May 2018 at the First Annual NWU Teaching and Learning Conference at the North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa.]

I would like to take the opportunity to thank the conference organisers for the invitation to join your celebrations. Looking at the conference program of yesterday and today, it is clear that there is a lot of passion and commitment in this room. The variety of topics presented at this conference reveal ample evidence of honest reflections to, among other things, increase the quality and effectiveness of learning experiences, for both student and faculty. Please accept my apologies for not being able to attend yesterday as I had another commitment.

Organising conferences is an increasingly difficult task. Not only does one have to ensure that the budget of the conference breaks even or even make a profit, but one also needs to attract scholars and practitioners who are willing to use the provided space to share their research and to network. And then, of course, there is access to free WiFi and good food… Many a conference has failed not because of the quality of the keynotes or the presentations and networking, but due to the WiFi failing or the sandwiches being late for teatime.

Except for budget and attendance figures, choosing keynotes and getting their commitment to honour the invitation, is part of the more tricky parts of organising a conference. So what does one look for when inviting a keynote? Most probably the first criterion is to invite someone who has scholarly gravitas in the field (and more about that later). But conference organisers are also looking for someone who can provoke, entertain, have a sense of humour and, importantly, keep to the allocated time. While I cannot judge my own gravitas in the field, I certainly aim to entertain you, to share some provocations, …and to keep to the allocated time. But there is something that is bothering me…

Having acknowledged the challenges in organising conferences and in choosing keynotes, I want to use this opportunity to briefly reflect on the irony that it is 2018 in South Africa, and we still have a conference with all of the keynotes being male and white.

On being a white, male keynote

When I received the invitation to keynote at this event, I took up this matter with the conference organisers and I was informed that one keynote withdrew at a very late stage and they could not find available candidates that were not white and male. I was torn between declining the invitation or accepting the keynote but then use the opportunity to highlight the lack of diversity.

It would have been disingenuous if I did not use my invitation as white, male scholar to raise awareness that we have an urgent obligation to seriously rethink whose voices are amplified at academic conferences, whose voices are shunned or overlooked and what that means not only for the conference itself, but also for transformation in South African higher education.

With these brief remarks out of the way, I would love to share some thoughts around the title for this presentation – “Faculty as quantified, measured and tired: The lure of the red shoes”

There was once a little girl…

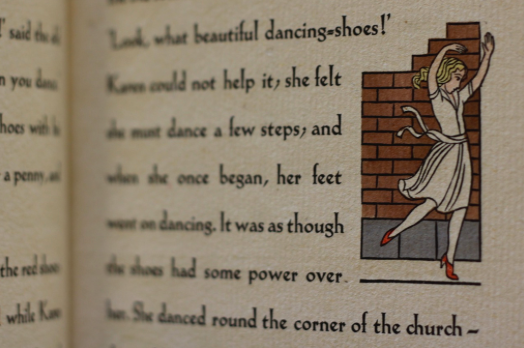

[Image credit]

Hans Christian Andersen started his tale of “The red shoes” with the words “There was once a little girl …” The girl, Karen was fascinated with a pair of red shows which she was determined to wear to church. Of course, society frowned on any female wearing red shoes, no matter what the occasion, but this did not deter the girl from wearing the red shoes… The object of her desire soon turned into a nightmare as the red shoes acquired a life of their own and could not stop dancing. The initial excitement of having red shoes that could not stop dancing soon wore off when she realised that she was not able to take off the shoes, no matter how hard she tried. She even misses her adoptive mother’s funeral because she just could not stop dancing. Unable to stop dancing, the girl begs an executioner to cut off her feet so that she could, at last, come to rest and not dance. But even when detached from her body, her feet with the red shoes could not stop dancing… The fairy tale ends with the girl finding redemption and “Her soul flies on sunshine to Heaven, where no one mentions the red shoes.”

Since Andersen penned down the fairy tale, the tale was adapted into plays, movies and ballets.

Recently, in a production by Matthew Bourne, the tale was adapted to tell the tale of a young ballerina who aspired to become world-class. As if, in an answer to her prayers, she is offered a pair of red shoes. After the initial rise in fame, she realises to her horror that the object of her fascination turned into horror as she could not take off the shoes. The red shoes took over control of her life. It goes without saying that the ballet does not have a fairy tale ending.

Academics with red shoes…

The tale by Hans Christian Andersen resonates with many faculty, on many different levels. Many of us can identify with the intoxicating enticement of receiving accolades from students and management applauding you as a good teacher who goes out of his or her way, the lure of being a rated scholarand internationally acknowledged, using the latest technologies in your teaching or just knowing that you are keeping abreast in your field.

Academics are also required to publish in high-impact journals, participate in various committees and task teams, strategic and operational planning sessions, grow an international reputation, excel in academic citizenship and lead community engagement projects. Not to mention teaching online and being available to students (and management) 24/7/365.

Making matters more complex is the phenomenon that higher education institutions have become obsessed with a variety of seemingly mindless rituals of verification, obsession with reporting and perpetual cycles of restructuring and change.

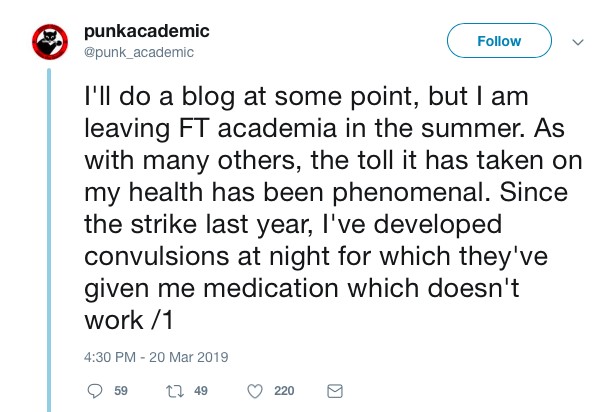

Many faculty are left breathless, anxious and increasingly demoralised.

Like the girl in Anderson’s fairy tale, many faculty discover there is no way to take off the red shoes and stop dancing. The band plays on… The tune does not change, the beat just gets faster.

Higher education is brimming with notions like “innovation”, “excellence”, “student satisfaction”, “unity”, “ratings” and “rankings”, and of course, “change”… As faculty and staff, we are called upon to embrace institutional change as if change is always an unqualified good and, of course, painless. While there are very few (if any) academics, administrative and support staff in higher education who will dispute the fact that they cando things more effectively, do them differently and most probably also, do differentthings; we often underestimate the impact (and pain) these changes will have on not only whatwe do, but also on who we are.

At this point of this reflection it is important to note that my intention is not to allocate blame on anyone, whether to the executive or middle management of our organisations, or administrators or rating and ranking agencies. Allocating blame will not necessarily help.

There is also a danger in painting the current challenges many faculty face as a crisis. While I would propose that the current situation has all the characteristics of a crisis, there is a danger that framing it as a ‘crisis’ leaves us disempowered, paralysed and despondent.

More important than allocating blame or to emphasise the crisis many of us experience, is to understand the field, the rules of the field, where these rules come from and how these rules impact on my being a researcher, being a scholar, being a teacher, parent, partner, … being human.

At the start of the keynote it is also important to acknowledge that it is almost obscene to reflect on the increasing pressures in academia while being tenured, white and male. The challenges facing female scholars from all races, as well as black, Indian and coloured faculty in a still untransformed South African higher education sector, are immense.

My own discomfort with being measured and quantified, pales in comparison to their experiences.

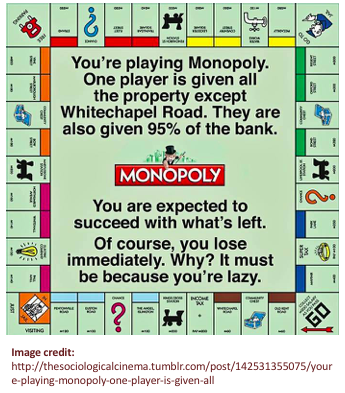

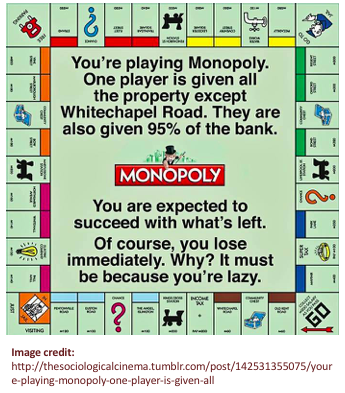

Female scholars of all races and Black, Indian and Coloured scholars enter the field of higher education as faculty and find the field hostile. It is like playing Monopoly where one player is given all the property except Whitechapel Road. They are also given 95% of the bank. They are expected to succeed with what’s left. Of course, many of them lose immediately. Why? It must be because they are lacy.

Many young scholars entering disciplinary fields just don’t have the necessary capital (whether social, disciplinary and institutional) to confront the orthodoxies in departments, disciplines and institutions and formulate alternative narratives, processes and procedures.

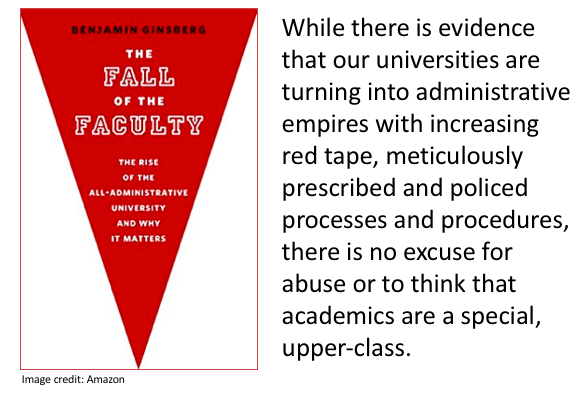

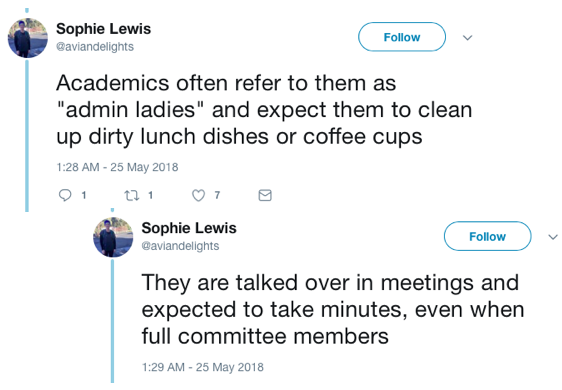

ALLOW WE TO DIGRESS FOR A MOMENT:It is important to note that while I specifically focus on faculty, I do not want to perpetuate the notion that faculty is a special category of staff, somehow more superior than administrative and support staff.

The abuse many administrative staff experience at the hands of faculty is simply unacceptable.

In this keynote, I will attempt to map some of the trends in international and South African higher education and reflect on how these changes impact on faculty identities, their expertise and their roles. Once we understand the field, meet the rule makers and their beliefs, we can consider the cost of (not) taking off the red shoes.

So how do we understand …

The fact that increasing number of faculty is experiencing burnout, anxiety and vulnerability?

How do we understand that many faculty are permanently and increasingly anxious, just not having enough hours in a day?

How do we understand that many faculty are permanently and increasingly anxious, just not having enough hours in a day?

The increasing concerns about overwork?

How do we understand the increasing surveillance of staff as part of performance management?

How do we understand the immense levels of demoralisation that many experience in their jobs?

How do we understand the immense workload and stress that borders on the inhumane?

To make sense of the experiences of faculty and other staff in higher education, we need to understand how the field of higher education shapes us, forms us, deforms us.

In order to explore ways to resist, to reclaim our humanness, our passion for teaching and research, it is crucial that we have a critical understanding of some of the factors that shape the field of higher education.

Higher education as field

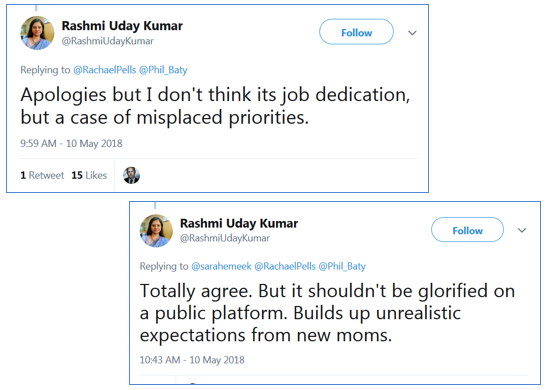

One possibility in helping us to understand not only what is happening, but also to explore how we can resist what is happening, is to explore higher education as a field.Think for one moment of a sports field, whether hockey, soccer or rugby.

In order for me to participate in a particular sport, I need to know what the field looks like, what the rules are, how many players there are on the field, and how to distinguish my own team members. I also need to understand what my position on the field entails, what is expected of me, how my position on the field speaks to my talents and skills, and how (and when) to respond to the ball coming in my direction.

The work of Pierre Bourdieu provides us with one possible lens on how to understand higher education and specifically, the role of faculty. Bourdieu (1984) proposed that we can understand practices and individual’s agency through the following formula:

Let us start with the field. The field does not refer to a pastoral field, but to a battlefield where various stakeholders lay claim to the field. Suffice to point to some of the trends currently impacting on the role of faculty in higher education:

Nothing illustrates higher education as assembly line better than the 1995 article by Hartley – “The McDonaldisation of higher education“. In the article he points out how higher education are increasingly required to do more with less, to expect funding to follow performance rather than precede it, and to realise that it costs too much, spends carelessly, teaches poorly, plans myopically, and when questioned, acts defensively (Hartley, 1995, p. 412, 861). In higher education as McDonalds, students are customers, teaching and learning have become assembly lines, and every attempt is made to work faster, more efficient, and cut down on the ketchup.

Since the publication of Hartley’s article, there are various scholars who map the impact of the dominant models of neoliberalism and its not-so-humble servant – managerialism – on higher education (Deem, 1998; Deem & Brehony, 2005; Diefenbach, 2007; Peters, 2013)

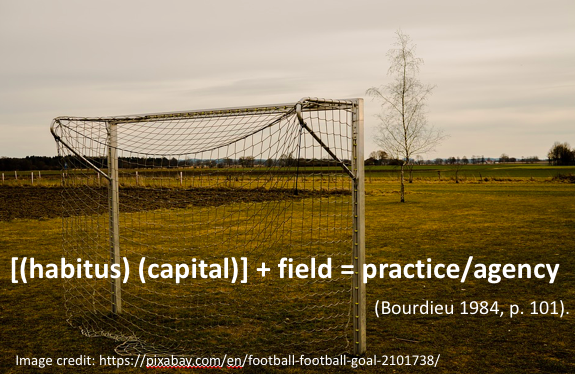

- There is talk of “academic capitalism” (Rhoades & Slaughter, 2004) where academics “sell their expertise to the highest bidder, research collaboratively, and teaching on/off line, locally and internationally” (Blackmore 2001, p. 353; emphasis added)

- “… the academic precariat has risen as a reserve army of workers with ever shorter, lower paid, hyper-flexible contracts and ever more temporally fragmented and geographically displaced hyper-mobile lives” (Ivancheva, 2015, p. 39)

- In 2012, of the 5 million professors in the US, 1 million are adjunct professors appointed on a contract basis (Scott, 2012)

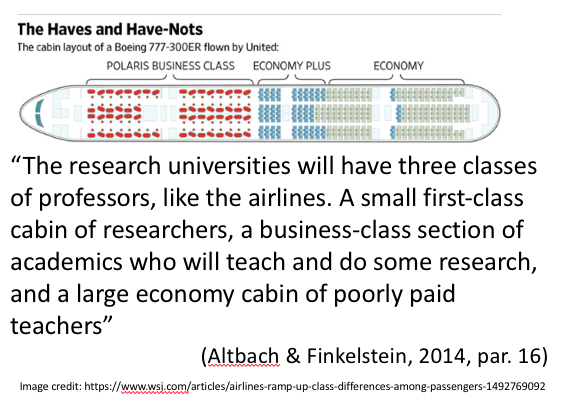

Let us also not forget how global university rankings are changing higher education. Competing in these rankings permeate everything we do – from who we recruit as students, how many applications we reject, how we value teaching compared to how we value research, and the monetary value of the research grants we bring in.

[Altbach & Finkelstein, 2014]

In a powerful book by Michael Power – “The Audit society. Rituals of verification” he exposes how the current culture of managerialism, performance management, and the quantification of everything result in perpetual rituals of verification. While there is criticism against the bookthat has reached almost iconic status with its claim of an “audit society”, reading his book requires us to take a step back and ask: What is going on?

Within the context of the field, I would like to turn our attention now to two specific aspects of the current obsession with numbers in higher education namely, the power of numbers or in the words of David Beer (2016) “Metric Power” and secondly I would like to point to the issue of performativity and fabrications of value (Ball, 2004).

In his book, “Metric power” (Beer, 2016), David Beer explores not only our current obsession with measuring everything, but also questions some of the founding assumptions behind our beliefs in measurement and point out a number of implications of these beliefs. He does, however, move beyond just mapping the data and measurement landscape and petitions us to look how our metrics and quantification of everything shape us.

In life outside the academe, we measure our calorie intakes, the number of steps we take, the routes we run and walk (and share them on social media). We get notifications on our mobiles if anything is posted anywhere, when news breaks, when someone shared a new picture on Instagram and we look enviously at the number of followers on our Twitter and Facebook accounts. In the institutions where we are scholars, we count, we report on these measurements and our value in the organisation and in the broader context of higher education is based on the number of citations, the number of keynotes per year, the number of publications, the number and size of our applications for research grants, the number of mentees and how many of them have applied for research grants, the number of graduate students we supervise, the number of committees we serve on and how many articles we reviewed for how many journals.

We need to slow down and consider Beer’s words –

“Metrics facilitate the making and remaking of judgements about us, the judgements we make of ourselves and the consequences of those judgements as they are felt and experienced in our lives. We play with metrics and we are more often played by them” (p. 3).

Beer (2016) places his exploration of metrics in terms of the debates on governmentality and power, in the broader context of political structures and constellations such as neoliberalism and neoliberalisation with its main emphasis on ‘markets’ as governing principle.

In the context of neoliberalism, “Competition is not just an organising principle but also a virtue” (p. 12). Beer (2016) quotes Brown who argues that “all conduct is economic conduct; all spheres of existence are framed and measured in economic terms and metrics, even when those spheres re not directly monetised” (Brown, 2015, in Beer, 2016, p. 22).

Except for the fact of seeing everything through an economic lens, “measures define what is true and then are used to verify the truth” (Beer, 2016, p. 28).

We need to understand this in the context of the role metrics play in higher education and in the lives of faculty. Of greater concern is to acknowledge that our obsession with metrics points to particular way of seeing knowledge.Metrics and the measurement points to an ontological turn in higher education, where the way we see and use metrics and data, changes our definitions of value, knowledge and being.

Our measurements – what they measure and how the phenomenon is measured – enable “norms to be cemented and versions of normalcy to be reified against which people can then be judged” (Beer, 2016, p. 43). In his work, Beer (2016) explores the thinking of Hacking (1990) and Porter (1986, 1995) on the impact of statistical thinking on society and how “what it is to be considered normal was established in the numbers” (p. 46). For example, he quotes Porter (1995, in Beer 2016, p. 49) who said …

“A decision made by the numbers (…) has at least the appearance of being fair and impersonal. Scientific objectivity thus provides an answer to a moral demand for impartiality and fairness. Quantification is a way of making decisions without seeming to decide. Objectivity lends authority to officials who have very little of their own.”

It is therefore important to acknowledge how the seeming objectivity of numbers that form the basis for most, if not all, evidence-based management approaches, “brings legitimacy and projects authority onto those who use them” (Beer, 2016, p. 50). Except for the fact that seeing the world through numbers, and defining ‘true’ knowledge based on numbers, we also have to consider how those using and requiring measurements use these numbers to cling onto their power and to perpetuate a certain view of the world as ‘normal’.

As our measurements normalise a particular view of the world, it is important to note that there are many things that cannot (and possibly should not) be measured. “Those things that cannot be counted are rendered invisible, and those that can be counted achieve visibility” (Beer, 2016, p. 59). We must therefore take care and accept responsibility that “numbers have the power to force us to overlook aspects of the social world” (Beer, 2016, p. 60). <

Hence measurement is powerful not just for what it captures and the way it captures it, it is also powerful because of what it conceals, the thing it leaves out, devalues, or ignores. In other words, measurement draws attention to certain things, illuminating them in a very particular light, whilst pulling our gaze away from other aspects of the social and the personal…” (Beer, 2016, p. 60).

It is outright dangerous to use our measurements, our numbers as the only ‘truth’, as neutral and removed from ethics and/or politics.

“As compliment, it can have many uses, but when used alone, when the world is reduced to numbers, a measure, to what is calculable and laid before us; when humans are summed, aggregated and accounted for; then much remains forgotten, unsaid, concealed” (Elden, 2006, in Beer, 2016, pp. 59-60).

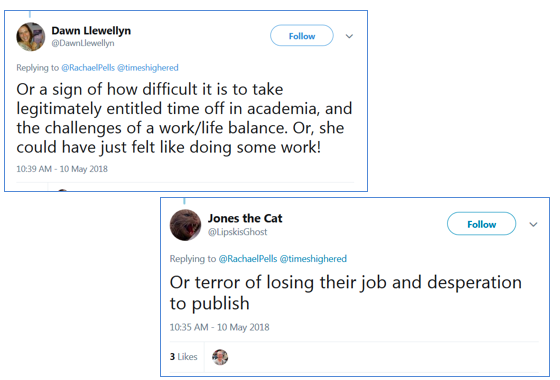

Let us now briefly turn to higher education as a “performative society” (Ball, 2004). Ball (2004) refers to performativity as a “technology, a culture and a mode of regulation, or even a system of ‘terror’ …, that employs judgements, comparisons, and displays of means of control, attrition, and change” (p. 144). Like Beer (2016), Ball (2004) points to the fact that we are increasingly constituted by the how we are quantified and we become our numbers and lose ourselves in the process.

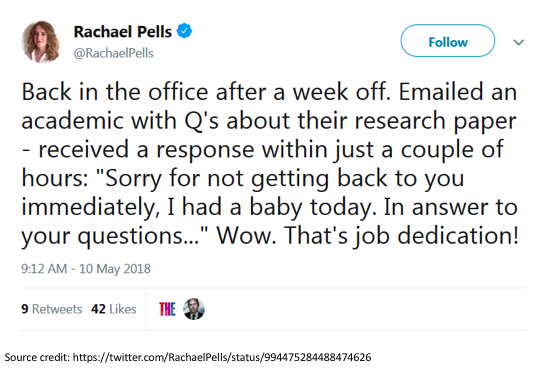

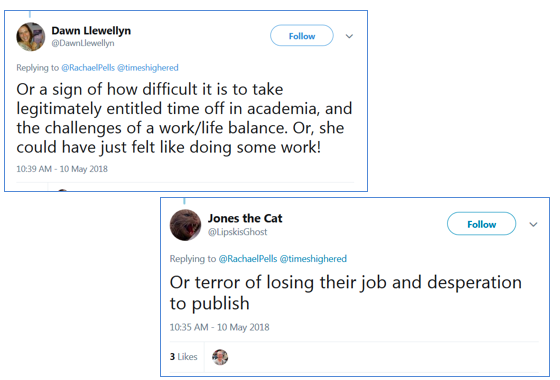

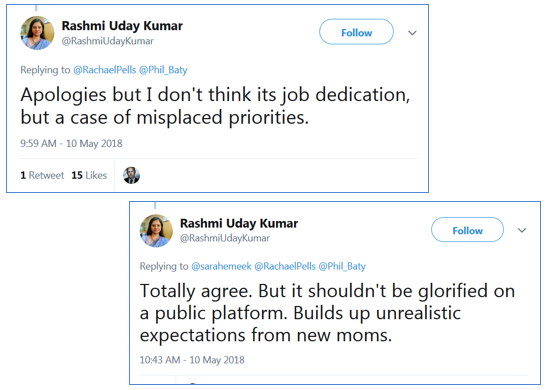

We are constantly performing never knowing when we are good enough and when the curtain will close for the last time. We depend on the applause, on the reviews and we are constantly compared to those who came back early from maternity leave, or those who work Saturdays and Sundays. We operate “within a baffling array of figures, performance indicators, comparisons and competitions – in such a way that the contentments of stability are increasingly elusive, purposes are contradictory, motivations blurred and self-worth slippery” (Ball, 2004, p. 144)

“You start to query everything you are doing – there’s a kind of guilt in teaching at the moment” (Jeffrey and Woods, 1998, in Ball, 2004, p. 145). “Here then is guilt, uncertainty, instability and the emergence of a new subjectivity – a new kind of teacher” (Ball, 2004, p. 145). Possibly the worst part is that “Some of the oppressions I describe are perpetrated by me. I am agent and subject within the regime of performativity in the academy” (Ball, 2004, p. 146).And so we start to fabricate our lives – how many hours we’ve taught, how many of our students passed, how many articles we have published, how many applications have we submitted for external funding, how many journal articles have I reviewed, how many Masters and PhD students am I supervising, how many, how many, how many…

So we perform, we produce a spectacle of Excel spreadsheets that we submit quarterly. And so I become alienated from myself, what I really love about teaching, what excites me about research.

I am emptied out.

“We choose and judge our actions and they are judged by others on the basis of their contribution to organisational performance” (Ball, 2004, p. 147).

But then our fabrications need to be sustained, they assume a life of their own and demand more and more of our attention. “Authenticity is replaced by plasticity…” and the red shoes take on a life of their own.

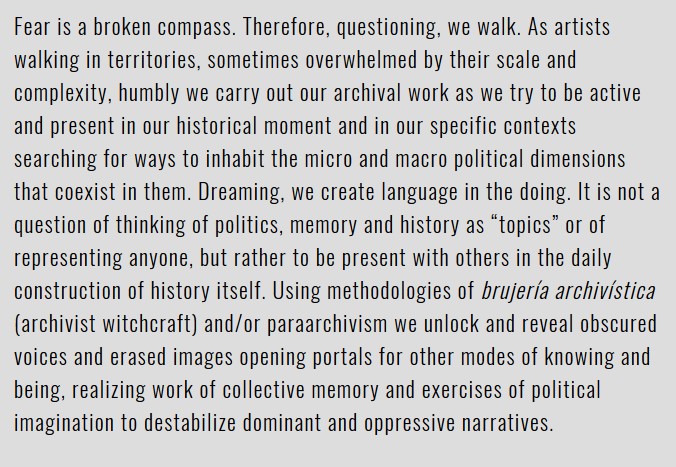

Talking back/Advocacy

Is there a way to claim back our academic identities, our dreams, our time? Is it possible to stop living fabricated, empty lives, take off the red shoes and stop dancing?

In this last part of the keynote, I would like to turn our attention to strategies to claim back our lives, to move from quantified to qualified lives. And no, there is not easy way.

In a recent publication, “The slow professor. Challenging the culture of speed in the academy” (Berg & Seeber, 2016), they map the current crisis in the professoriate but are very careful to open up the crisis to look for opportunities to talk back, to claim back stolen identities, stolen dreams, stolen time.

Two other publications worth noting are:

- Leibowitz, B., & Bozalek, V. (2018). Towards a Slow scholarship of teaching and learning in the South. Teaching in Higher Education, 1-14.

- Mountz, A., Bonds, A., Mansfield, B., Loyd, J., Hyndman, J., Walton-Roberts, M., … & Curran, W. (2015). For slow scholarship: A feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: an international E-journal for critical geographies, 14(4).

Berg and Seeber (2016) in their book “The slow professor” warn that the notion of the professor as an “autonomous, tenured, afforded the time to research and write as well as teach” is facing extinction (referring to the work of Donoghue, 2008) (in Berg & Seeber, 2016, p. 5). While they do acknowledge that the notion of a ‘crisis’ and reference to ‘extinction’ creates a sense of urgency – there is a danger that we feel overwhelmed and powerless. And therefore the notion of resistance has so far been underplayed.

Despite the title of the book, “The slow professor”, Berg and Seeber (2016) state that what they propose is “not a simple matter of ‘slowing down’ but rather it is more fundamentally an issue of agency” (p. 11). Their book is not a collection of nostalgic ideas about university life in the past, but rather a tentative, yet powerful reflection on claiming back our lives, our worth, our dreams.

With regard to academics constant complaint of a lack of time, they stat that “Academic culture celebrates overwork, but it is important that we question the value of busyness. We need to interrogate what we are modelling for each other and for our students” (p. 21). None of the self-help literature on how to manage your time more effectively really helps. “The real time issues are the increasing workloads, the sped-up pace, and the instrumentalism that pervades the corporate university” (Berg & Seeber, 2016, p. 25).

So what is left for us to do:

- We need to get offline. Yes, this is not being anti-technology. To the contrary. In my own scholarly praxis I’ve found my networks on Twitter and Facebook incredibly valuable and I cannot be a scholar without these connections. As scholar I think I live online – it sustains my curiosity, provides stimuli and inspiration and my networks support me. But… Recently I discovered that my attention span has diminished. I could not read a scholarly article in one sitting. I would read one page (if I was determined) before looking for something else (most probably online) – another source, another brief scan of a news article, printing yet another article. I got scared. I turned on the brakes. I paid attention to what was happening. And I took control. I still consider being online an essential part of who I am as scholar. But I am very aware of how it feeds a particular attention deficit.

- We need to do less – “Time management is not about jamming as much as possible intoyour schedule, but eliminating as much as possible fromyour schedule so that you have time to get the important stuff done to a high degree of quality and with as little as stress as possible” (Rettig, 2011, in Berg & Seeber, 2016, pp. 29-30)

- We need regular sessions of timeless time

- We need timeouts

- “We need to change the way we talk about time all the time” (Berg & SEEBER, 2016, p. 31)

I concur with Berg and Seeber (2016) that we can slow down, that there are some things we can take control of. But there is a danger that in doing everything we can to adapt to the madness, the perpetual quantification and numbers-as-value, that we forget the need to confront the system that perpetuates and sustains this madness.

We can become stuck in self-care…

In a provocative post by Benjamin Doxtador (January 13, 2018) he explores the possibilities and limitations of self-care amid the increasing demands on students and faculty. While we should look for innovative ways to look after ourselves, “this logic of efficiency can also be used by governments and institutions to increase both class sizes and labor demands on teachers.”

“Self-care then becomes another demand to put on our to-do-list, part of our ongoing responsibilities to become optimal workers. This quickly slides into a kind of deficit thinking about teachers who are unable to ‘keep up,’ especially when combined with the idea that the best teachers run on pure passion.”

Benjamin Doxtador quotes Yashna Padamsee who, says, “let’s not get stuck here.” He emphasises that “While self-care is important, it doesn’t fundamentally interrupt and challenge the larger structural injustices in the system.” There is a need to move beyond the conversations surrounding self-care to considering how we can and should care for one another in communities of practitioners/activists. “We need to move the conversation from individual to collective. From independent to interdependent.”

Being part of communities of/that care will prevent self-isolation as we all face, as individuals, the power of metrics, the reality that much of what we do are invisible and worthless for those in power. Doxtador concludes his blog post by stating –

“We should never underestimate how dangerous acts of caring and solidarity are to neoliberalism’s drive to privatize our struggles.”

As I wrap up this keynote, I would like to refer to an amazing presentation by Jesse Stommel “Centering Teaching: the Human Work of Higher Education” (May 28, 2018). Jesse formulates a power counter-narrative amid and against the increasing bureaucratisation of pedagogy and teaching and how the mechanisms dehumanise both teachers and students.

(In)conclusion

It is important to note that I am not against ‘measurement’ and the use of statistics and numbers in higher education. It is, however, crucial to slow down and consider how our current obsession with numbers and measurements in higher education have dramatic implications for how we understand knowledge and ‘truths’ in the world. We have to accept the fact that our measurements define what is acceptable and what is normal, and as such, then institutionalise and perpetuate particular beliefs about normalcy. Not only do we need to accept the implications that we our measurements only take into account that which can be measured, that which is visible to our instruments and that there is a lot of things that cannot be measured and that are invisible. The fact that these things cannot be measured does not make them of lesser value. We must also withstand attempts to define proxies for what is, in their essence, immeasurable and invisible.

The fact that Anderson’s fairy tale ends in a combination of horror and salvation, may not be of much comfort. But at least we can take a good look at the red shoes, the exhilaration of the dance, the panic, the exhaustion and the cost of (not) wearing them…

Photo by ICSA on

Photo by ICSA on