- This blog contains text and some of the images used for the invited seminar, UNESCO Chair on Open Distance Learning, University of South Africa (UNISA), Wednesday 12 August 2020

This reflection flows from an editorial I wrote for a Special Issue of the International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education with the theme “Towards a critical perspective on data literacy in higher education. Emerging practices and challenges”, to be published later this year.

Key takeaways

- Some students are more vulnerable, at particular points, in their journey than others, whether temporary or occurrent.

- Their vulnerabilities are often linked to or caused by vulnerabilities in the system (ICT, faculty). We therefor have to think of student vulnerability in terms of the broader eco-system consisting of human and non-human actors, processes, systems and imaginaries.

- We have a responsibility and moral mandate to identify and support the vulnerable, and address or ameliorate the impact of the factors causing the vulnerability*. [*Terms and conditions apply. While some of students’ vulnerabilities are linked to the actions or in-actions of other human or non-human actors in a particular context, there are layers of vulnerability that fall outside the locus of control or mandate of higher education].

Key questions

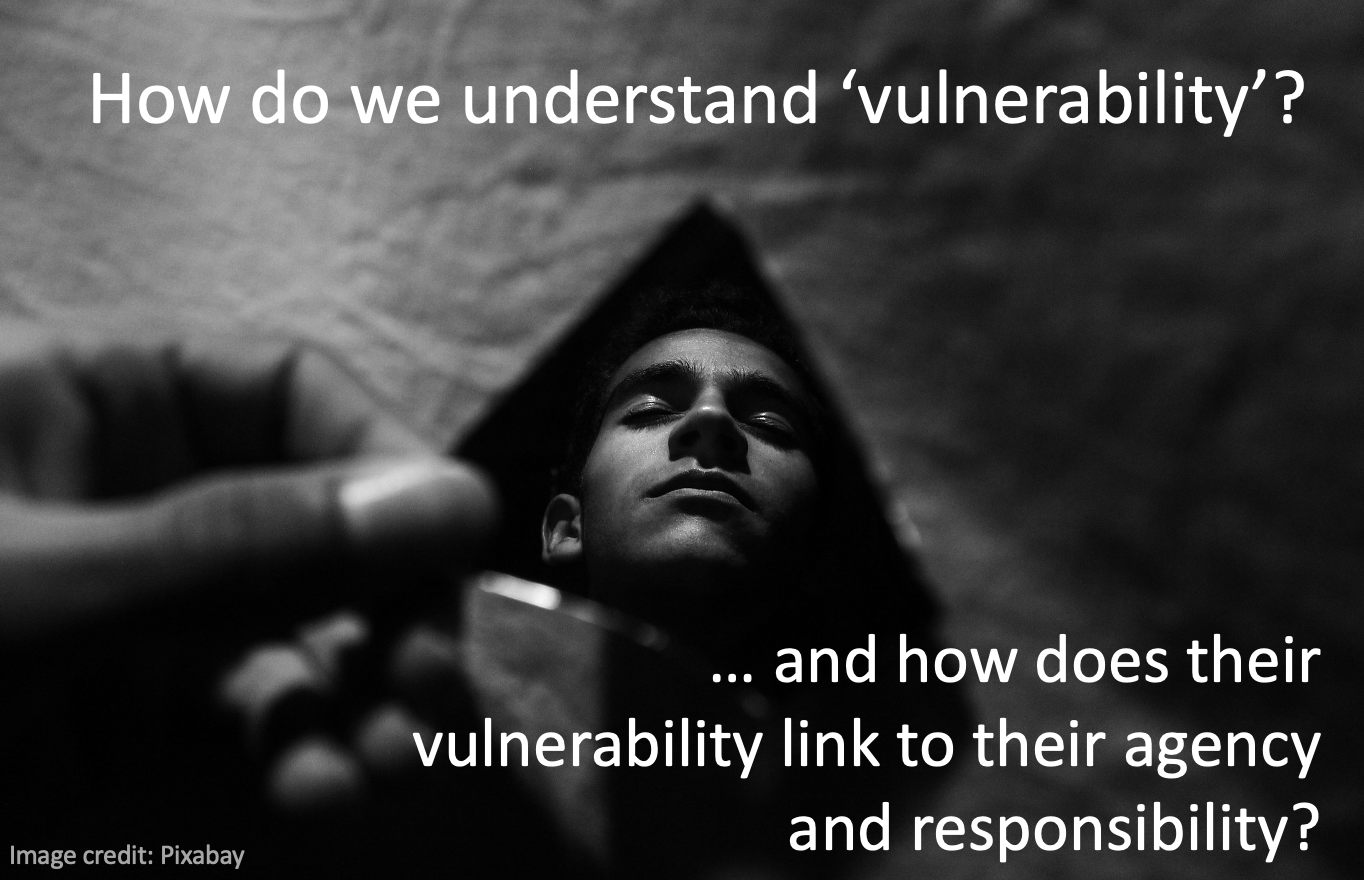

- How do we understand (student) vulnerability?

- How do we identify these vulnerabilities – what data do we use and why?

- What are our assumptions about these data/categories?

- How can we prevent vulnerabilities in our systems and processes to impact or exacerbate their vulnerabilities?

Introduction

Before COVID-19, when we would have thought about or spoke about vulnerability, we may have thought about it as a relatively far away concept, for many of us. Thinking about vulnerability called forth images of old people walking with walking sticks or in frail care, babies not being able to care for themselves, people with disabilities, and people living in shacks. We may have called to mind images of refugees, people left vulnerable by war or economic hardship. The list would have been endless – but the list would mostly have been about individuals ‘out there’.

When the COVID-19 pandemic started to be a global phenomenon and we saw the overflowing hospitals and cemeteries in Italy, once again, it we all prayed that it would somehow spare the African continent. As the pandemic unfolded, we smiled at pictures of people panic buying toilet paper, and we joked about how awkward some people looked with masks.

And then it arrived. The panic buying (and I am not talking about alcohol) started with shops running out of masks, sanitisers, and toilet paper. Suddenly we were all vulnerable. But even though we were all vulnerable, some were more vulnerable than others. Early evidence showed that people living with co-morbidities like diabetes, TB, HIV and individuals older than 60 were at greater risk to contract the disease. What became very clear early on, is that your socio-economic security and well-being, access to credit and healthcare, running water, and foot security before the pandemic determined, to a great extent, your rate of socio-economic survival during the pandemic.

As government responded to the pandemic with various strategies to prevent the spread of COVID-19, and introduced social distancing, the regular washing of hands and closed small shops and businesses, it became very clear that many of these regulations were non-sensical in neighbourhoods with no running water, where extended families shared small houses, and where the survival of a household depended on the earnings of selling an array of fruit, vegetables and Grandpas on street corners. In an attempt to make people less vulnerable, these steps actually made people more vulnerable.

COVID-19 brough our understanding of vulnerability and how fragile we all actually are to the fore. It also provided us with a disturbing realisation of though we are all vulnerable, some are more and differently vulnerable than others. For many of us the vulnerability during COVID-19 will pass, for many COVID-19 will leave them more vulnerable than ever before.

In thinking about student vulnerability in higher education, COVID-19 may have provided us with a more nuanced understanding of vulnerability, the different layered-ness of vulnerability, how specific events can, overnight, change your vulnerability status, and how in our responses to ameliorate the vulnerability of targeted individuals, may actually increase their vulnerability.

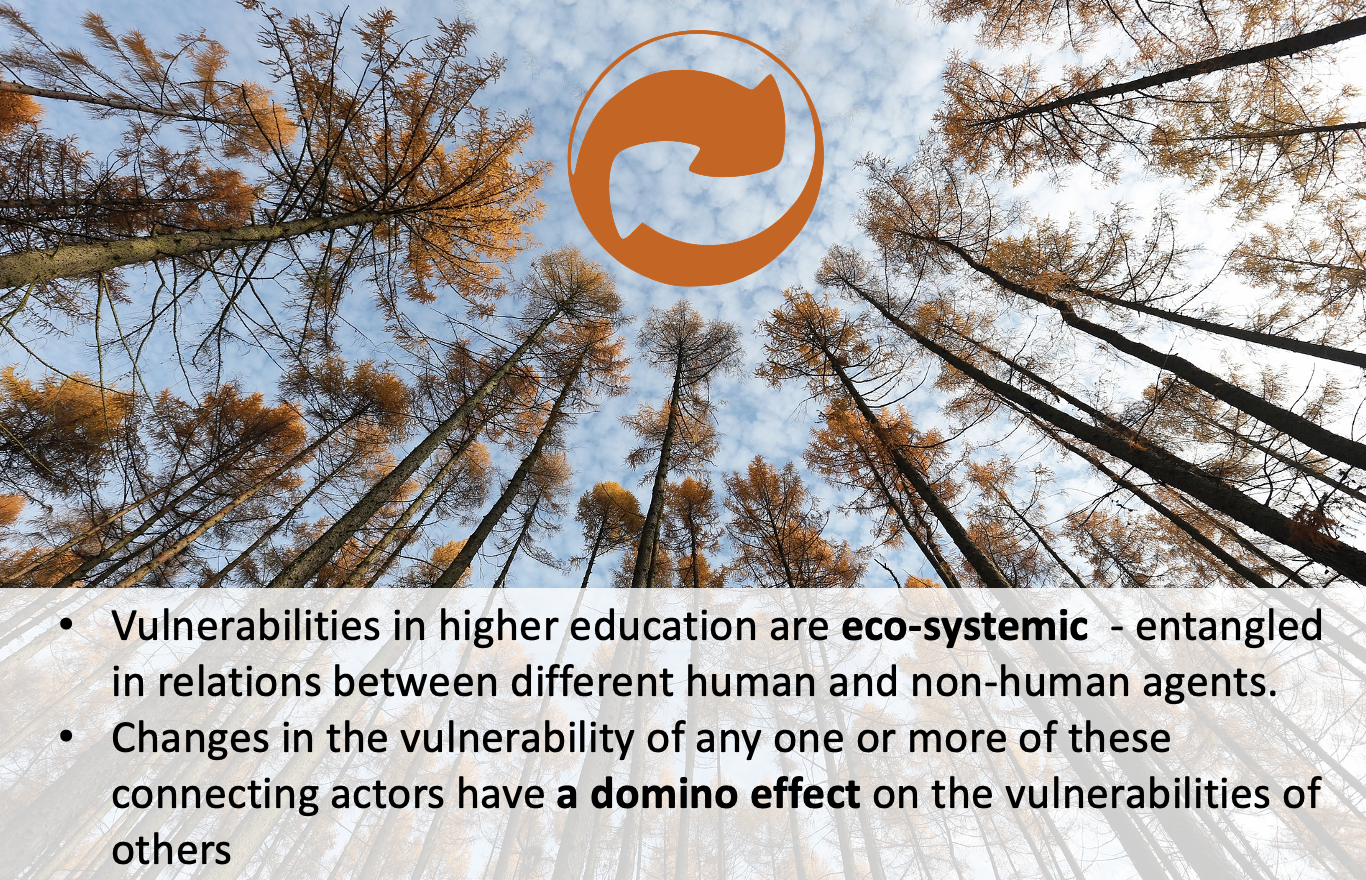

But COVID-19 has also foregrounded that it is not only (some) students that may be vulnerable, but that many faculty, administrative staff were also and continue to be vulnerable. The vulnerability also include systems, processes, capacity, and policies. There were many examples of how the challenges faculty faced in teaching from home impacted on students who waited longer for feedback, or did not get someone to respond to their queries. We saw how vulnerabilities collided and increased as our ICT systems could not handle the amount of uploads, students could not get hold of faculty and faculty could not get hold of ICT.

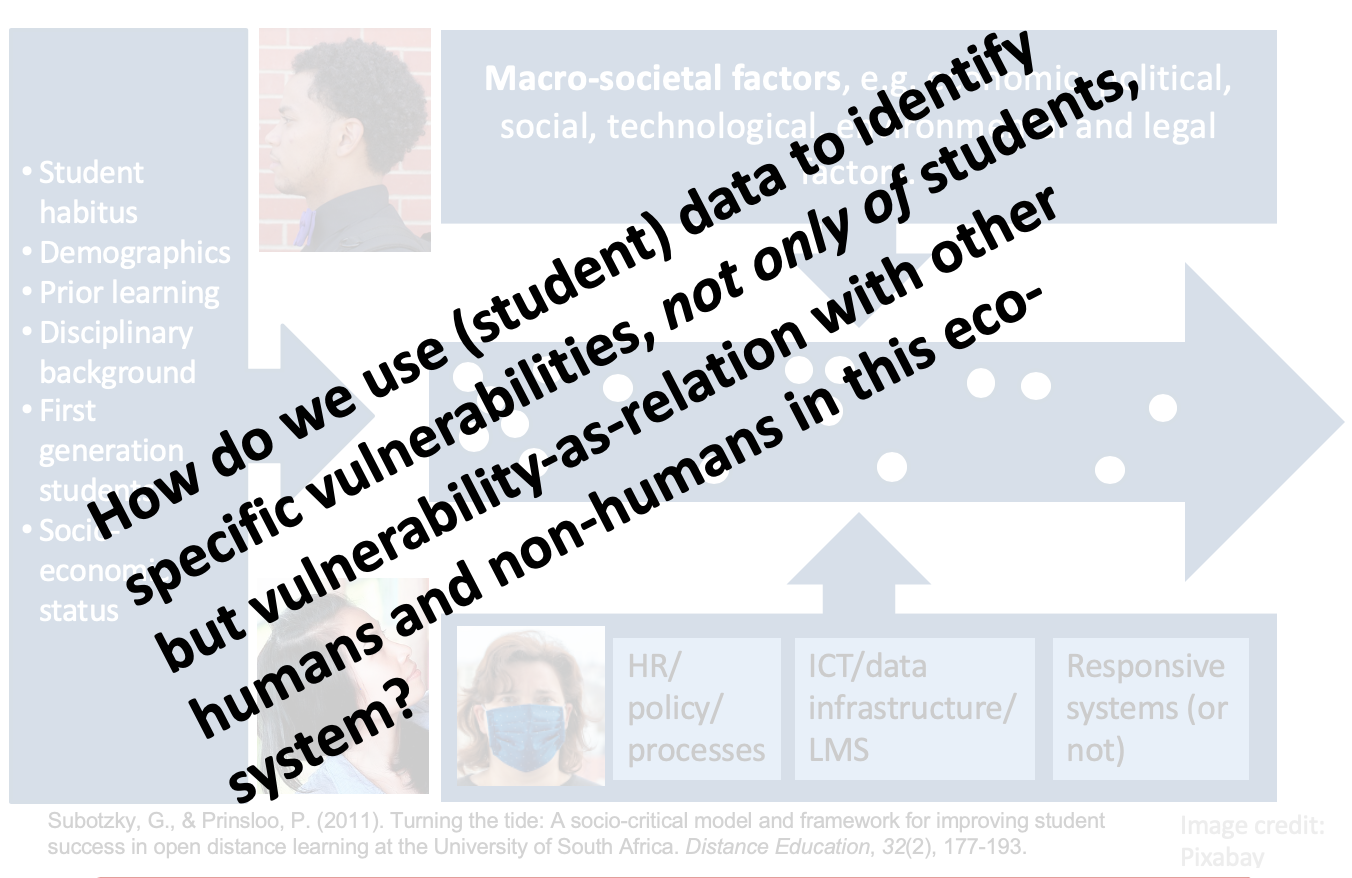

We have to start thinking about vulnerability in terms of an ecosystem – with different human and non-human agents are connected, in relation with one another, and where changing circumstances in any of the vulnerabilities of any of the human and non-human actors, have an impact on the vulnerabilities of others, and actually, the whole ecosystem.

Thinking of vulnerability eco-systemically

So, what are the implications of thinking about (student) vulnerability and the ways it manifests using an eco-systemic lens?

Thinking of students’ vulnerabilities as their fault, of characteristics they don’t have

Much of the research on student success or failure, retention or attrition, focuses on what students have, don’t have, what students need to do, in order to be successful. We measure their readiness, their competencies or lack of the necessary skills and understandings. We blame them for not trying hard enough. We advise them to have a growth-mind set and we measure their resilience and grit. We hardly ever consider their vulnerabilities in terms of the ecosystem. We never seem to consider how their vulnerability, however temporarily, results from or is exacerbated by an ICT system crashing, a query that does not get answered, a lack of formative assessment with formative feedback (not in general, but per student). We never consider how students’ vulnerability is related to the staff: student ratios at Unisa, the immense workloads our faculty carries, negotiating time between teaching several courses, supervision, research, community engagement and academic citizenship. We never consider how students’ vulnerabilities are made worse by the vulnerabilities inherent in the broader ecosystem such as the sustainability and cost of connection to the internet.

Vulnerability is relational.

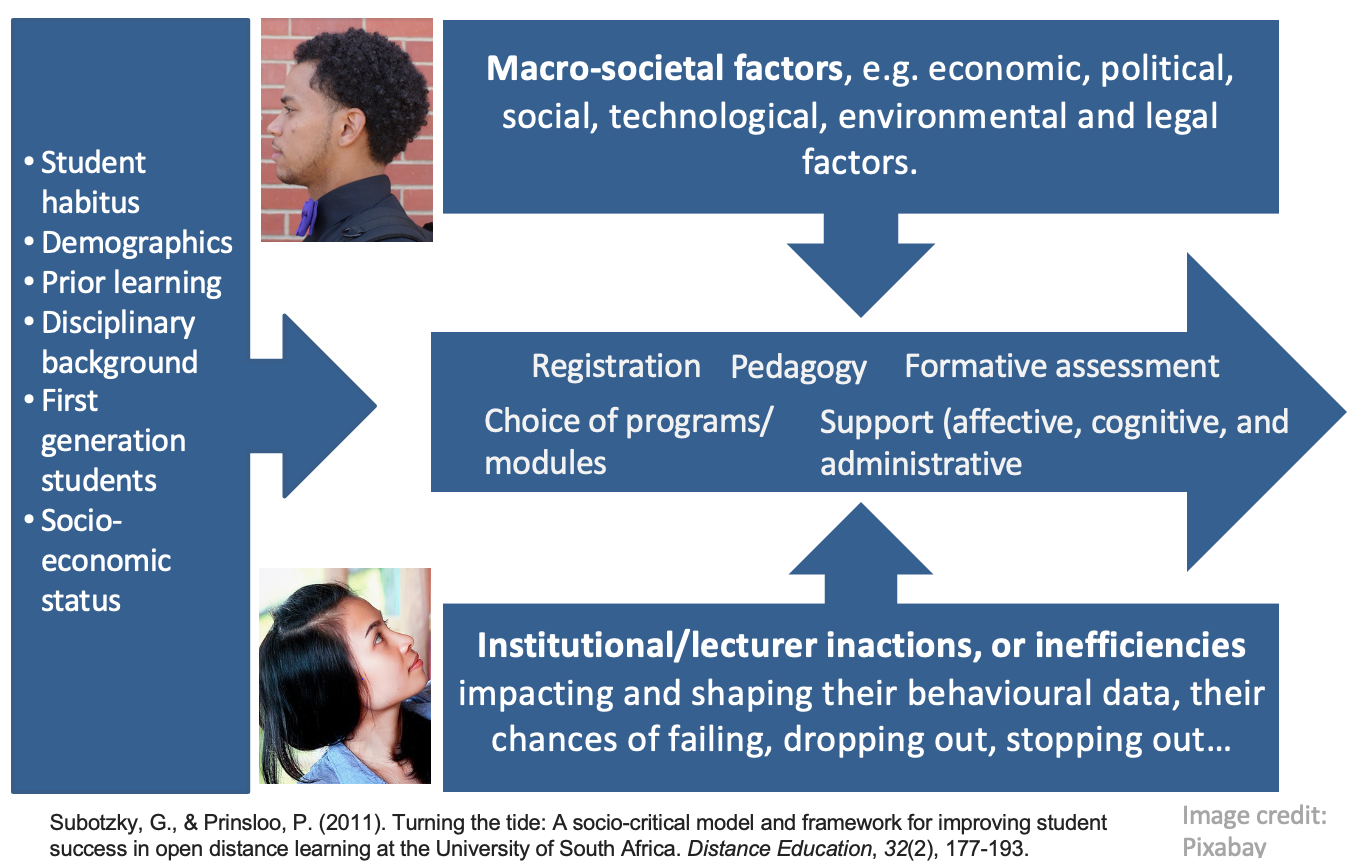

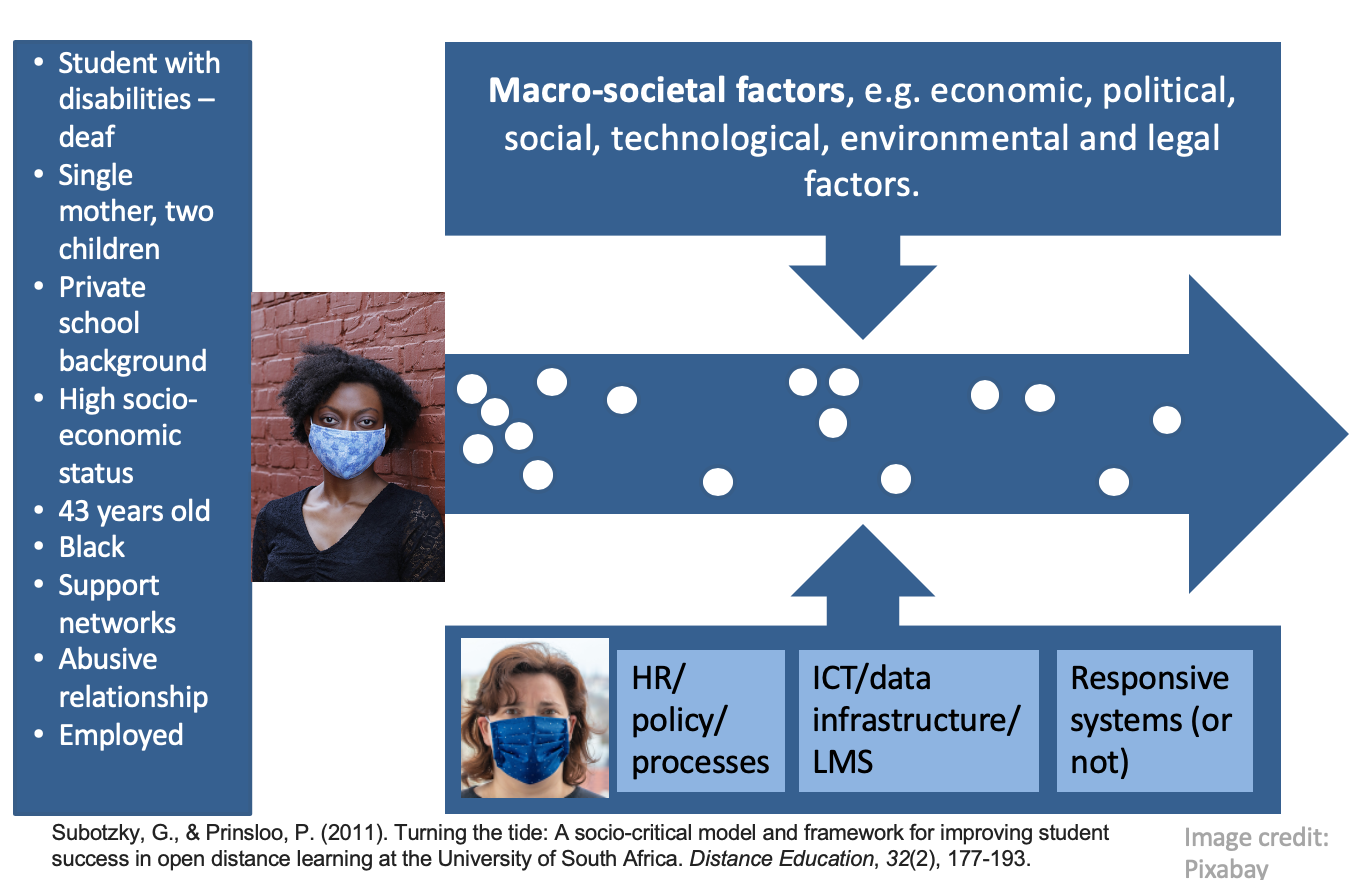

Taking my cue from the socio-critical model of Subotzky and Prinsloo (2011), students enter higher education with a range of experiences, dispositions, capital, self-efficacy, agency, and from disparate socio-economic circumstances. They register, and choose programs and modules/courses for which they may (not) be prepared, encounter curricula and pedagogies that may (not) appeal to their prior learning and/or interests. Normally formative assessment should pick up disciplinary or other needs, but often, in large cohorts, the feedback on these formative assessment are general, and less personal feedback. Throughout this journey or ‘student walk’ students may (not) receive affective, cognitive and administrative support.

Often, in learning analytics, we would collect, measure, analyse and use student data as if they are the only role players and the data will not, necessarily account for (in)efficiencies and/or (in)actions on the side of academic departments, faculty, ICT and the broader institutional culture.

The data we have to our disposal may also not provide us with insight in broader macro-societal changes and trends that impact on students and the institution, e.g. pandemics, political unrest, economic downturns, etc.

Student retention, success, attrition, failure, drop-out and/or stop-out therefore has to be understood as emerging from multiple, often mutually constitutive factors in the nexus between student habitus, capital, agency and disciplinary and institutional contexts and arrangements (e.g. responsiveness, epistomological access, student: staff ratios, etc) as well as macro-societal forces.

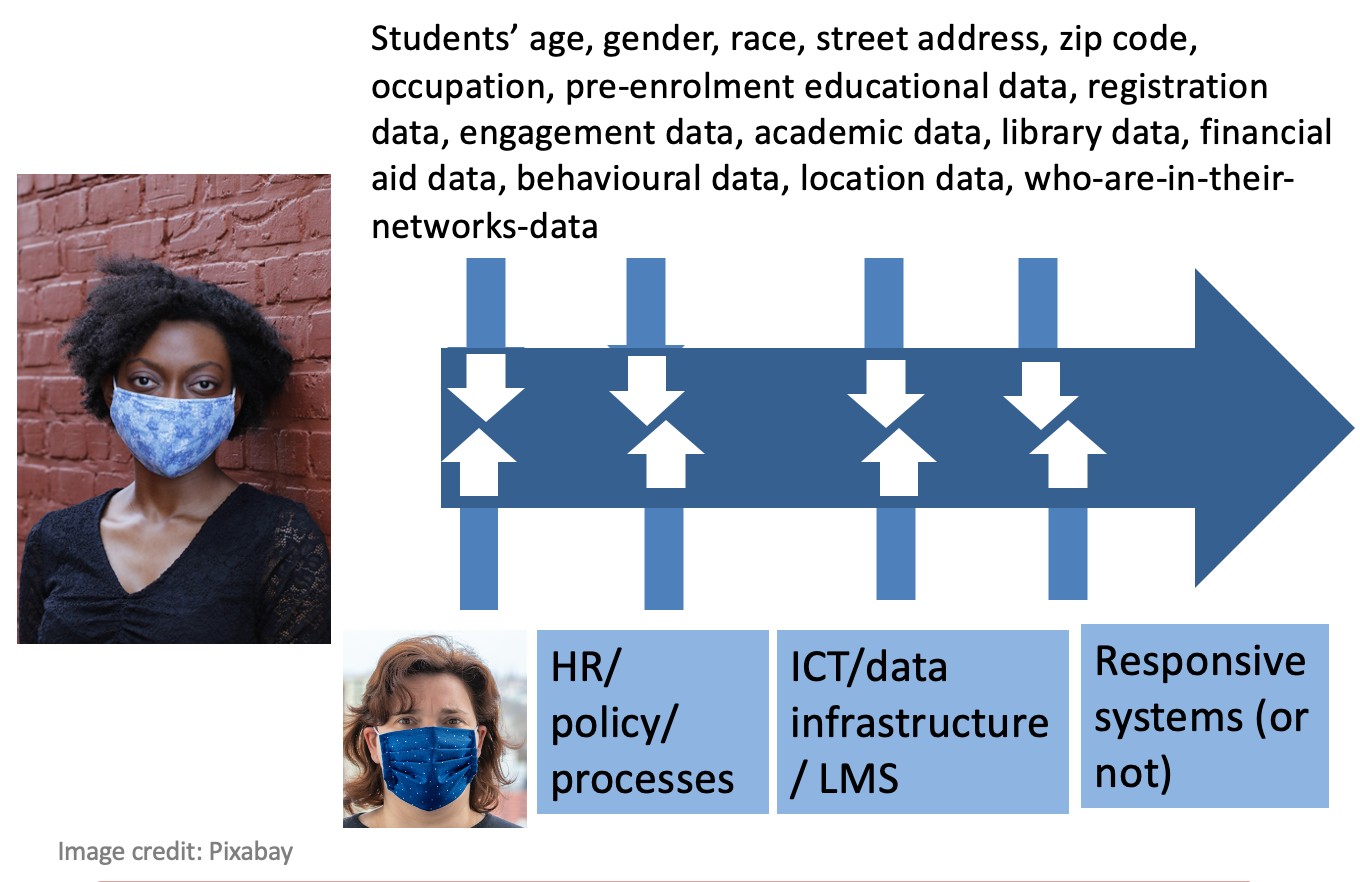

Thinking of student vulnerability in terms of an eco-system, means that student vulnerability is linked to, and entangled in the vulnerabilities of the lecturer, the department and institution’s policies and processes, ICT and data infrastructures, and the responsiveness of systems. We often speak of students-at-risk, or student vulnerability without considering student vulnerability as assemblage, of intersecting lines, emerging like a rhizome.

Vulnerability, in general, and especially student vulnerability in learning analytics can be w considered, “under-theorised” (Mackenzie, Rodgers & Dodds, 2014, p. 2; Prinsloo & Slade, 2016). Being identified as vulnerable, in general, means membership of a sub-group, as non- conformance to the criteria of the ‘normal’ or ‘non-vulnerable’ or being ‘deficient’ in some respects (Broughan & Prinsloo, 2020) and as such, vulnerability becomes a ‘label’ (Luna, 2009) and increasingly a permanent, digital part of an individual’s profile (e.g. Mayer-Schönberger, 2010). The data and categories used to define student vulnerability are often “zombie categories” (Archer & Prinsloo, 2020; Guillion, 2018) – “categories from the past that we continue to use even though they have outlived their usefulness and even though they mask a different reality” (Plummer, 2011, p. 195).

In the context of education, these labels accompany students for a particular course or semester, or even for the duration of the program, and may follow them long after graduation. Except for considering the permanence of such a label (and its implications – see Mayer-Schönberger, 2010), there is a real danger that in an attempt to address students’ vulnerability, instead of amelioration, students’ vulnerability may become pathogenic (Prinsloo & Slade, 2016). It is therefore crucial to consider student vulnerability in the context of student agency (Jääskelä, Heilala, Kärkkäinen & Häkkinen, 2020), as well as found in the nexus of students’ habitus and agency, disciplinary and institutional contexts – efficiencies, responsiveness and resources, and macro-societal factors (Subotzky & Prinsloo, 2011). While some of the discourses on student agency emphasise grit, persistence, and a ‘can do’ attitude, often forgetting that student agency is not only situated in a particular context and flow from their habitus, but is, as such, a constrained agency (Subotzky & Prinsloo, 2011) and entangled in intergenerational structural arrangements and power (Strayhorn, 2014).

A critical consideration of the complexities in the nexus of student vulnerability, agency and learning analytics can easily start with any of the three elements, let us begin with unpacking (student) vulnerability by briefly considering three different reflections on vulnerability – the taxonomy of vulnerability proposed by Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds (2014), the work of Luna (2009, 2019), and Butler (2012, 2016) before we consider the implications for student vulnerability, agency and learning analytics.

Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds (2014) propose a taxonomy of vulnerability comprising “three different sources of vulnerability (i.e., inherent, situational, and pathogenic) and two different states of vulnerability (i.e., dispositional and occurrent)” (p. 7). Inherent vulnerability refers to “ sources of vulnerability that are intrinsic to the human condition. These vulnerabilities arise from our corporeality, our neediness, our dependence on others, and our affective and social natures” (p. 7; emphasis added). The second source of vulnerability is situational or context where one’s vulnerability “…may be caused or exacerbated by the personal, social, political, economic, or environmental situations of individuals or social groups. Situational vulnerability may be short term, intermittent, or enduring” (p. 7). Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds (2014) acknowledge that the inherent and situational categories are not “categorically distinct … Both inherent and situational vulnerability may be dispositional or occurrent” (p. 8; italics in the original). Of particular importance to this reflection is Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds’ (2014) claim that “Inherent and situational vulnerability give rise to specific moral and political obligations: to support and provide assistance to those who are occurrently vulnerable and to reduce the risks of dispositional vulnerabilities becoming occurrent” (p. 8). The third source of vulnerability, according to Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds (2014) is pathogenic vulnerability that “may also arise when a response intended to ameliorate vulnerability has the paradoxical effect of exacerbating existing vulnerabilities or generating new ones” (p. 9).

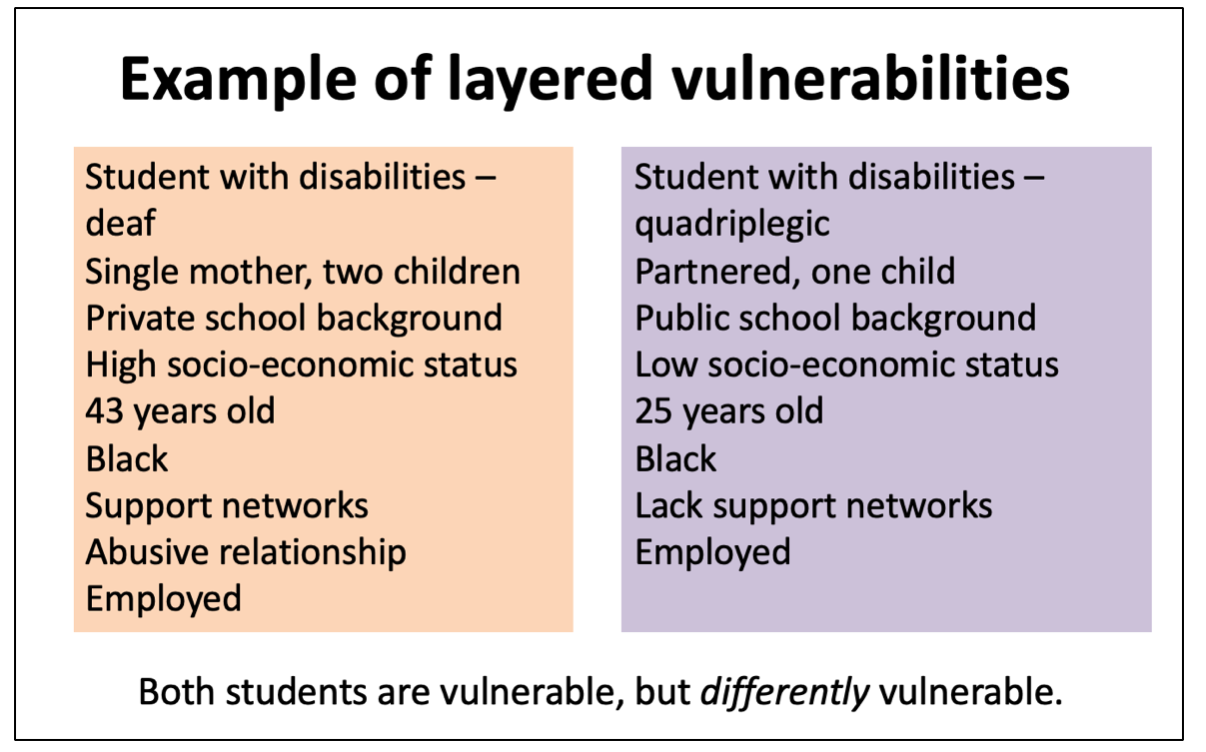

In her mapping of vulnerability as ‘layered’, Luna (2009) states that considering ‘vulnerable groups’ in research, can be linked back to the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research, 1979) which mentions specific groups as examples of vulnerable groups “such as racial minorities, the economically disadvantaged, the very sick, and the institutionalized”, who, “given their dependent status and their frequently compromised capacity for free consent, they should be protected against the danger of being involved in research solely for administrative convenience, or because they are easy to manipulate as a result of their illness or socioeconomic condition” (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research, 1979, p. 9). As Luna (2009) warns, the treatment of vulnerability as the result of a combination of characteristics, results in “vulnerable as a fixed label on particular subpopulations” and “suggests a simplistic answer to a complicated problem”(p. 124). Addressing individuals’ vulnerability may require “more than one answer” as “Different types of vulnerabilities can overlap”(Luna, 2009, p. 124). Vulnerability should therefore best be considered as “layers” –

The metaphor of a layer gives the idea of something “softer,” something that may be multiple and different, and that may be removed layer by layer. It is not ‘a solid and unique vulnerability’ that exhausts the category; there might be different vulnerabilities, different layers operating. These layers may overlap: some of them may be related to problems with informed consent, others to social circumstances. The idea of layers of vulnerability gives flexibility to the concept of vulnerability (Luna, 2009, p. 128).

To illustrate Luna’s (2009) proposal of ‘vulnerability as layers’ let us consider students with disabilities. Not only do the specific nature of their disabilities make a difference to their vulnerability in specific contexts, students with disabilities from well-resourced socioeconomic backgrounds may be differently vulnerable than students with disabilities from poor socioeconomic backgrounds. Even then, there may be further layers that disrupt homogenous understandings of vulnerability as label. One may find a student with disabilities from a well-resourced socioeconomic background, but who is, at the same time, suffers from an abusive relationship, or may have experienced personal loss. Luna (2009) therefore suggests that vulnerability is, per se, relational – “That is, it concerns the relation between the person or a group of persons and the circumstances or the context” (p. 129). Vulnerability may therefore not be an inherent or permanent characteristic by emerge as a result of “a particular situation that makes or renders someone vulnerable” (Luna, 2009, p. 129). Once the situation changes or the individual is found or located in a different context, the nature and scope of vulnerability may change or disappear. Luna (2009) therefore proposes that an individual does not, per se, become, vulnerable, but rather acquire “ a layer of vulnerability; she is vulnerable in some particular aspect that is the result of the interaction of her particular circumstances and her own characteristics” (p. 129). To summarise, Luna’s (2009) proposal to see vulnerability not as a fixed category, label and “as a permanent and categorical condition… that persists throughout its existence” (p. 129) may help us to understand vulnerability in a more nuanced way. Understanding vulnerability as layered furthermore “challenges idealized views of the agent, human agency, and even justice that are so common in contemporary ethics” (Luna, 2009, p. 134).

In her 2012 essay, Butler considers “… whether any of us have the capacity or inclination to respond ethically to suffering at a distance and what makes that ethical encounter possible, when it does take place. The second is what it means for our ethical obligations when we are up against another person or group, find ourselves invariably joined to those we never chose, and must respond to solicitations in languages we may not understand or even wish to understand” (p. 134). The first question Butler (2012) asks raises the interesting issue whether “proximity imposes certain immediate demands” (p. 135) and what happens to these demands when the vulnerable person or group is some distance away, or even when the vulnerable is not of our race, nation or culture, or even enemy. Butler (2012) suggests that “these are ethical obligations that do not require our consent, and neither are they the result of contracts or agreements into which any of us have deliberately entered” (p. 135).

In this particular essay, Butler (2012) enters in ‘conversation’ with Levinas and Hannah Arendt. From Levinas’s work, Butler (2012) states that our ethical obligations are, “strictly speaking, precontractual” (p. 140) even when we do not know the other, or choose the other.

As such, the “Other has priority over me” (Butler, 2012, p. 140) and is, per se, asymmetrical. Because the Other is vulnerable, this demands a unexpected, unsolicited and pre-contractual response from me, and therefore, makes me vulnerable.

Both Levinas and Arendt, according to Butler (2012) contest the idea that ethical obligations arise as a result of contracts, deliberately and voluntarily agreed to between one another. For Arendt, our ethical obligation towards the Other’s vulnerability arise precisely from the fact that we “Not only do we live with those we never chose and with whom we may feel no immediate sense of social belonging, but we are also obligated to preserve those lives and the open-ended plurality that is the global population” (Butler, 2012, p. 144). Our ethical obligations to one another arise not because of agreements, choice or love, but exactly because we “have no choice” (p. 150) no matter how we “rail against that unchosen condition, we remain obligated to struggle to affirm the ultimate value of that unchosen social world” (p. 150).

Both Levinas and Arendt, according to Butler (2012) contest the idea that ethical obligations arise as a result of contracts, deliberately and voluntarily agreed to between one another. For Arendt, our ethical obligation towards the Other’s vulnerability arise precisely from the fact that we “Not only do we live with those we never chose and with whom we may feel no immediate sense of social belonging, but we are also obligated to preserve those lives and the open-ended plurality that is the global population” (Butler, 2012, p. 144). No matter how one defines ‘we’, “we are also those who were never chosen, who emerge on this earth without everyone’s consent and who belong, from the start, to a wider population and a sustainable earth” (p. 146). Interestingly, Butler (2012) then maps uncomfortable terrain about the ethical obligations that arise from “situations of antagonistic and unchosen modes of cohabitation” (p. 150). Our ethical obligations to one another arise not because of agreements, choice or love, but exactly because we “have no choice” (p. 150) no matter how we “rail against that unchosen condition, we remain obligated to struggle to affirm the ultimate value of that unchosen social world” (p. 150).

In Butler’s (2016) article – “Rethinking vulnerability and resistance” she destablises the notion of vulnerability and states that we have to see and theorise vulnerability as relational and as “a relation to a field of objects, forces, and passions that impinge upon or affect us in some way” (p. 16). She points out the reality that some dominant groups “can use the discourse of “vulnerability” to shore up their own privilege” (p. 13). As example, she mentions

In California, when white people were losing their status as a majority, some of them claimed that they were a “vulnerable” population. Colonial states have lamented their “vulnerability” to attack by those they colonize, and sought general sympathy on the basis of that claim. Some men have complained that feminism has made them into a “vulnerable population” and that they are now “targeted” for discrimination. Various European national identities now claim to be “under attack” by new and established migrant communities (p. 13).

Butler (2016) concludes that we should understand vulnerability as having “a way of shifting, and since we may not like some, or even many of the shifts it makes, we may find ourselves somewhat awkwardly opposed to vulnerability. Of course, that is a rather funny thing to say, since we might conjecture that any amount of opposition to vulnerability does not exactly defeat its operation in our bodily and social lives. (p. 13). And while there are many legitimate criticisms of how vulnerability is appropriated and used, Butler (2016) moots that “vulnerability is not a subjective disposition” (p. 16) but relational. Vulnerability is also “neither fully passive nor fully active, but operating in a middle region” (p. 17).

For example, Butler (2016) asks “What about the power of those who are oppressed? And what about the vulnerability of paternalistic institutions themselves? After all, if they can be contested, brought down, or rebuilt on egalitarian grounds, then paternalism itself is vulnerable to a dismantling that would undo its very form of power”(p. 13). In this one sentence, Butler destabilises vulnerability in a number of ways. She firstly asks how being vulnerable and oppressed, changes the power of the oppressed, or whether their vulnerability informs and in a certain way, instigates their agency. Secondly, Butler (2016) points to the reality that institutions and systems of oppression themselves can be vulnerable. And, what happens when vulnerable peoples address systems of oppression – “do they not establish themselves as something other than, or more than, vulnerable? Indeed, do we want to say that they overcome their vulnerability at such moments, which is to assume that vulnerability is negated when it converts into agency? Or is vulnerability still there, now assuming a different form?” (p. 13).

Let us start, for a moment, with learning analytics’ central concern to improve learning and to assist instructors to teach better, support teams to support more strategically and more effectively, and for students to be provided with analyses to help them make better informed choices (Gašević, Dawson, & Siemens, 2015; Siemens & Long, 2011). In order for learning analytics to realise its potential, it needs data – student data, to be more exact. Of specific interest at this point is considering that learning analytics focus on student data, and exclude from analytics data generated by instructors, events outside of the scope of learning management systems, and data arising from macro-societal events and impacts, influencing students’ journeys, but that falls outside the “data gaze” (Beer, 2019). Except for the reality that some of the default positions in learning analytics are contestable (Archer & Prinsloo, 2020) and that students’ learning journeys are translated and voiced-over in institutional accounts of their learning (Broughan & Prinsloo, 2020), students are often categorised as vulnerable using incomplete, tentative data and bracketed into zombie categories that may follow them, like zombies, long after they have graduated. But, let us start with vulnerability.

Some students are more vulnerable than others – from the start – whether due to personal histories and demographics, socio-economic circumstances, gender, race and the list can go on. Students enter the playing field of higher education, and different disciplines not from the same starting point and as Mackenzie, Rogers, and Dodds (2014]) indicated, their vulnerability will be differentiated and arise from a variety or combination of inherent, situational, and pathogenic sources found in either dispositional or occurrent states. There is a real risk that learning analytics hold students accountable or take factors into account for classifying them as vulnerable and at-risk, over which students do not have any control. Learning analytics may furthermore treat vulnerability as a ‘label’ and permanent characteristic and address one of the many layers of vulnerability (Luna, 2009). It is also crucial to understand that vulnerability is context and time-bound and that though some vulnerabilities such as students with disabilities have a permanent character, other vulnerabilities may be temporal or context-specific. And as illustrated earlier, sharing one characteristic such as ‘disability’ does not mean equal and permanent vulnerabilities. Washington and Kua (2020) use the notion of “differential digital vulnerability” to describe “how vulnerable populations are disproportionately exposed to harm through data technology that seeks to promote a single point of social good” (p. 9). “We extend Wynter’s argument that categories of protectable life in social and economic systems imply categories of unprotectable life to technological systems. Our observations suggest that technological systems reveal differential vulnerability through digital representations” (p. 9).

Most of the work on student vulnerability and institutions obligations towards reaching out and supporting students with vulnerabilities, are founded on the contractual (legal, social and moral) agreement between institutions and students (e.g. Prinsloo & Slade, 2014, 2016; Slade & Prinsloo, 2013). Butler’s (2012) discussion of the work of Levinas and Hannah Arendt destabilises the contractual basis for ethical obligations and proposes that the vulnerable (student) ‘demands’ an unsolicited response, not because of a contractual agreement, and as such, renders the lecturer, support and administrative staff representing the institution, vulnerable. The fact that in identifying vulnerable students, institutions themselves become vulnerable resembles the research by Prinsloo and Slade (2017). But, while Prinsloo and Slade (2017) would have centred the institution’s vulnerability as a result of its contractual obligations towards students – to not only be responsive but also response-able, the work of Butler (2012) provides a different foundation than contractual, namely the duty of care that comes into being, because of sharing a space, a learning journey.

Lastly, we also have to consider Butler’s (2016) destabilising of vulnerability and consider how the status of being vulnerable plays out as a political construct in the nexus of political, economic, social, legal, environmental and technological contexts. It is therefore crucial to consider where our classification of some students as vulnerable, leave them and how their classification as ‘vulnerable’ can, and actually, should empower them and not take away their agency.

Using the example of one of the fictive female students discussed earlier, consider the different factors impact on this particular students’ vulnerability. Possibly, an institution would have classified her as ‘vulnerable’ due to her ‘disability status’. But such a categorisation is such a poor (an in my opinion, lazy) attempt to map her particular vulnerabilities as if they don’t come into being with her other inherent and situational vulnerabilities, and how her categorisation as ‘vulnerable’ may have been impacted upon by vulnerabilities in the rest of the eco-system. Should she become unemployed, this may change the total picture. Should she walk out of her abusive relationship, that will have a domino effect on the other layers of her vulnerability. Should the lecturer who deals with her own layers of vulnerability not respond to a request for a late submission of a compulsory assignment, one can just get a sense of how these vulnerabilities intersect.

The question is, what data points do we have in the journey of the student (not only student generated by the particular student) but also data of faculty responses, downtime of ICT systems, etc.? How do our categories represent the layers and the complexities or do our current categories distort our understanding of student vulnerability?

Towards a layered and eco-systemic view of (student) vulnerability

Accepting as point of departure the proposition of Mackenzie, Rogers and Dodds (2014) that vulnerability is undertheorised and that thinking of vulnerability as inherent, situational and pathogenic (as well as dispositional and/or occurent) can provide us a good starting point for moving towards the suggestion by Luna (2009, 2019) of vulnerability as layered.

So whereto from here? Luna (2019) identifies some very useful steps towards moving away from seeing vulnerability as an inherent characteristic of an individual and/or group, but rather as a set of layers resulting in a state of vulnerability. The first step, according to Luna (2019) is to identify the different intersecting layers. It is crucial to also map how the different layers resulting in more or less vulnerability play out in a particular context and what stimuli triggers the layers to assume different positions of permanence/importance. It is also important to explore and disentangle the ‘cascading of layers’ – how the layers interact and how one specific aspect of vulnerability may trigger a cascading of pathogenic vulnerabilities in a particular context (Luna, 2019). The second step is to rank the different layers resulting in vulnerability with regard to their harmfulness in a particular context. Of particular importance would be to identify those layers resulting in vulnerability that are cascading or that have a domino effect. These layers have a “differential strength and damaging power” and “We should consider the dispositional structure of layers of vulnerability and assess what stimulus conditions can trigger them (their presence and probability of developing). Stimulus conditions relate layers with the context, with the actual situation and possibility of occurrence” (Luna, 2019, p. 92). The third step is to identify those layers resulting in vulnerability that are cascading or that have a domino effect.

Of particular importance is Luna’s (2019) proposal that three kinds of obligations can be applied to and arise from the previous ranking of layers and to the identification of the various stimulus conditions. The first obligation is “not to worsen the person’s or group’s situation of vulnerability (be this with a protocol intervention or with a public policy). Thus, we should avoid exacerbating layers of vulnerability” (p. 93). The second obligation focuses on the eradication of layers of vulnerability. In cases where a particular layer of vulnerability cannot be eradicated, we should attempt to minimise the impact of these layers. “Finally, these obligations can be expressed through different strategies such as protections, safeguards, as well as empowerment and the generation of autonomy” (Luna, 2019, p. 93).